On

January 10 1778, John Houstoun was elected as the new Governor of Georgia.

Born at Frederica, he was a lawyer in Savannah — only 27 years old when

elected governor. Expectations were high as one on the Council of Safety

stated, “…We have some reason to expect Good order and harmony will succeed

the Anarchy and Tyranny which has so long distracted this unhappy State…”

Instead Houstoun became one of Georgia’s greatest disappointments in the

American Revolution.

The frontier between the Independent state of

Georgia and

the

Loyal

British province of

East Florida

was, for the first three years of the

American Revolutionary

War, the scene of ongoing cattle raids by the Loyalist Florida

Rangers and allied Indians. Political and military leaders in Georgia believed

that East Florida's capital,

St. Augustine,

was vulnerable, and repeatedly promoted expeditions to capture it.

The first two failures did not dissuade Georgians from a third attempt upon

Florida in 1778.

the

American Revolutionary

War, the scene of ongoing cattle raids by the Loyalist Florida

Rangers and allied Indians. Political and military leaders in Georgia believed

that East Florida's capital,

St. Augustine,

was vulnerable, and repeatedly promoted expeditions to capture it.

The first two failures did not dissuade Georgians from a third attempt upon

Florida in 1778.

The southernmost post in Georgia was Fort Howe (before the war known as Fort

Barrington),

on the banks of the

Altamaha River

above Darien, and the northernmost Florida outpost was at

Fort Tonyn,

near Kings, also called Mills, Ferry on the St. Marys River, in present-day

Nassau County. East Florida Governor

Patrick Tonyn

had under his command a regiment of Florida Rangers led by Lieutenant Colonel

Thomas Brown,

and five hundred British Regulars under the command of Brigadier General

Augustine Prevost.

Tonyn and Prevost squabbled over control of Brown's regiment, and disagreed on

how the province should be defended against the recent forays from Georgia.

Prevost was under orders to stay on the defensive, while Tonyn sought a more

vigorous defense. To that end Tonyn deployed Brown's force along the

St. Marys River,

which formed the border between Florida and Georgia. Brown and his men,

sometimes with support from

Creeks and

Seminoles,

engaged in regular raids into coastal Georgia, harassing the defenders and

raiding plantations for cattle to supply some of the province's food needs.

In February 1778, Georgia's assembly authorized Governor

John Houstoun

to organize a third expedition against East Florida. The expedition was

opposed by the Continental Army's Southern Department commander, Major General

Robert Howe,

who, like his counterpart Prevost, sought a more defensive posture. Plans

began to take shape in March taking on more urgency after Brown's Rangers

captured and burned Fort Howe in a surprise attack. After this occurred, the

Loyalists ranged freely throughout Georgia's backcountry, and began recruiting

in the upcountry of Georgia and the Carolinas. Their actions led Georgia's

leadership to conclude that a British invasion of the state was being planned,

and military preparations began to accelerate.

In addition to land forces, both sides had coastal naval forces to marshal.

Florida Governor Tonyn deployed several ships near Darien and in the

Frederica River,

separating

Saint Simons Island

from the mainland, seeking to neutralize the

row galleys

in the Georgia arsenal. Commodore Oliver Bowen commanded the Continental

Georgia Navy, consisting of six Continental galleys which defended the

intercoastal waterways, several provincial sloops brought supplies, and a few

privateers screened the open sea.

General Howe reluctantly agreed to support the expedition, and in early April,

Georgia's 500 Continental troops, under Colonel Samuel Elbert began to move

south, occupying the site of the burned Fort Howe on April 14.

The next day, Elbert

learned that four British vessels were sailing in the St. Simons Sound; he

sailed with three Georgia Navy galleys and captured three British ships near

the ruins of Fort Frederica. Elbert returned to Fort Howe to wait

for General

Howe and additional

troops. On May

10, they were joined by Howe with

detachment of 500 South Carolina Continentals and Artillery, and they

understood that General Andrew Williamson, leading 800 to 1,000 South Carolina

Militia, was en route to Fort Howe.

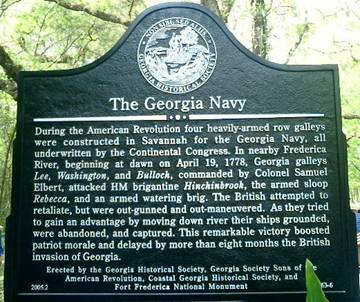

Frederica Naval Action

During the preparation for the Third Florida Expedition at Fort Howe, Elbert

learned on April 15 that four British vessels were sailing in the St. Simons

Sound, between St, Simons and Jekyll Islands. Sailing from Darien with three row galleys and artillery in another vessel,

Elbert’s flotilla arrived near

Fort Frederica

on April 18. (The “fort” was ruins of a British fort commanded by General

James Oglethorpe, beginning in 1736 until 1748, when a peace treaty was signed

with the Spaniards.)

Sailing from Darien with three row galleys and artillery in another vessel,

Elbert’s flotilla arrived near

Fort Frederica

on April 18. (The “fort” was ruins of a British fort commanded by General

James Oglethorpe, beginning in 1736 until 1748, when a peace treaty was signed

with the Spaniards.)

Colonel Elbert observed the attack preparations of the British, and at

daybreak on April 19, he initiated an attack against the British vessels as

anchored at the fort. Beginning at dawn on April 19, 1778, the Georgia Navy galleys: Lee, Washington, and Bulloch, attacked HM brigantine

Hinchinbrook, the armed sloop Rebecca, and another armed brig. The

British attempted to retaliate, but were out-gunned and out-maneuvered. As

they tried to gain an advantage by moving down river their ships grounded,

were abandoned, and captured. This remarkable victory, called the

Frederica

Naval Action, boosted patriot morale and delayed by more than eight months the

British invasion of Georgia.

The Third

Florida Expedition was better equipped than the other two. Armaments of all

sorts were in better supply than they had been, and even Artillery was

available. Nevertheless, such amenities as tents, camp kettles, canteens and

medicines continued to be almost nonexistent. As the

days passed at Fort Howe, the weather grew hotter, heavy rains seriously

endangered their ammunition, provisions ran short, morale deteriorated

steadily,

and there were frequent desertions, leading to at least eleven executions.

Governor John Houstoun had issued a proclamation calling on volunteers to meet

at a camp in Burke County, offering plunder that they may capture. On April

26, a force of 400 Georgia militia arrived at the camp, and General James

Screven was designated the military commandant of this contingent.

Governor Tonyn and General Prevost were aware of Howe’s progress, since

Brown’s Rangers and Indian forces continued to perform reconnaissance,

occasionally skirmishing with the Georgians and testing the security of their

camps. On one occasion, Brown was challenged by a picket, and followed by

horseman so closely that he was forced to drop his baggage, including his

coat, in order to escape into the swamp. The contents of the baggage revealed

that the Georgians had nearly captured Thomas Brown, himself. General Prevost

moved some of his Regulars forward to the Alligator Creek Bridge on the Nassau

River, placing most of them on the King’s Road, the main route to St.

Augustine.

Houstoun, who had no prior military experience, and his volunteer militia

finally reached General Howe’s troops on the St. Marys River in late June. At

this point the expedition almost broke down because General Howe and Governor

Houstoun could not agree on how to proceed. Houstoun wanted to march directly

toward St. Augustine, forcing a confrontation with the

Major

Prevost’s Regulars posted fifteen miles away on the King’s Road.

Howe wanted to first

attack

the East Florida Rangers and capture Fort Tonyn, ten miles downstream.

The

destruction of Fort Tonyn was one of the principal goals of Howe’s forces

invading East Florida. The fort, located in present-day Nassau County on the

south side of the St. Mary's River, about one mile east of Kings Ferry which

was also called Mills Ferry, had become a nuisance to Georgians because it was

a base for raids into that state by Brown's Florida Rangers as well as a haven

for fleeing Loyalists.

Raiding

parties of Florida Rangers and Indians fired on the Patriot forces, but their

greatest enemy was sickness.

General Howe’s expedition force finally began crossing the Altamaha on May 28,

but on June 6, about 300 Continentals became so sick that they returned to

Darien. The only encouraging note was Howe’s announcement on June 1 that

France had publicly acknowledged the independence of the United States of

America. In celebration, thirteen cannon were fired, and an issue of grog was

served to all.

Howe’s force moved very slowly, crossing the Satilla on June 21 and reaching

the St. Marys River on June 26.

The “usual order of march” was Georgia Continentals in the lead followed by

detachments of militia. The South Carolina Continentals trailed, sometimes as

far back as the previous river crossing. No one was sure where Williamson and

the South Carolina Militia were, except they were far behind.

On June

28, Howe’s Continentals finally began their march to Fort Tonyn. Their delay

had given Brown’s Rangers time to secure their equipment and burn the fort. On

June 28, Brown abandoned the fort and retreated into Cabbage Swamp, from which

they annoyed the Continentals as much as possible. The next day, June 29,

Howe’s force of over 400 men “captured” the fort and occupied it through July

11, 1778.

One of

Commodore Bowen’s Georgia galley had entered the Nassau River, and Continental

Colonel John White with ninety infantry and fourteen dragoons (light horsemen)

camped at Nassau Bluff near the mouth of the river. Prevost dispatched twenty

of his dragoons, and chased White’s men into the swamp. The British force

dined on the dinner that had been prepared for the Georgians, and then fell

back toward Alligator Creek

On June

30, Brown’s Rangers and Indians left Cabbage Swamp and marched toward the

Nassau River and encamped about six miles north of Prevost’s forces.

The way south from Fort Tonyn on the King’s Road led to a bridge across

Alligator Creek, a Nassau River tributary about fourteen miles away, where

British General Prevost had placed detachments of the 16th and 60th Regiments

of Regulars and

the

South Carolina Royal Americans

led by Daniel McGirth. They had constructed a redoubt of logs and brush with a

wide moat to defend the

Alligator Creek Bridge over that tributary of the Nassau River.

In addition to Brown’s 200 Florida Rangers, these forces

included 200 South Carolina Royal Americans

and 500 British Regulars, all under the command of General Prevost's younger

brother, Major

Marc Prevost.

Gov.

Houstoun opted to attack the Regulars at Alligator Creek; but first he ordered

General Screven’s 100 mounted Georgia Militia to pursue Brown’s Rangers as

they retreated south from Fort Tonyn toward Alligator Creek.

Brown continued moving down the road toward the bridge, but was surprised and

overtaken by Screven's militia shortly before he got there. As a result,

Brown's men were chased directly into the established British position at the

bridge.

There was some initial confusion, because neither Screven's nor Brown's forces

had conventional uniforms, so the British Regulars thought all of those

arriving were Brown's men. This changed quickly however, and a firefight broke

out. Prevost's Regulars quickly took up positions and began firing on

Screven's men, while some of Brown's men went around their flank.

Colonel

Elijah Clarke led 100 mounted militia on an attack on the weakest British

flank, so Screven could advance on the British front. The British Regulars and

Rangers met Clarke’s forces whose

horses penetrated the abatis of logs and bushes with great difficulty but

found the moat too wide to leap. Clarke was shot through his thigh, and barely

escaped capture. With the failure of Clarke’s attack, Screven’s main reserve

force did not attack

and many narrowly escaped being trapped before Screven ordered the retreat. In

the pitched battle, men on both sides went down;

the

Georgians’ loss being thirteen killed and several wounded, while the British

suffered nine casualties.

General

Andrew Williamson’s South Carolina Militia finally crossed the Altamaha River

in July. Like Houston, Williamson refused to co-ordinate with General Howe.

The Militia and Continentals were encamped about eight miles apart on

opposites of the St. Marys River.

Governor Houston urged General Howe to again attack the British at Alligator

Creek on July 2. Howe promptly agreed on the condition that Houston supply the

Continentals with rice. The Continental forces were out of rice, since a

supply galley had failed to arrive. Houston replied that he did not have

sufficient provisions with his own camp for the next day’s rations. The

Patriot attack did not take place.

The Continental force had been reduced by disease and desertion to only 400

effective soldiers; the

hospital returns contained one-half of Howe’s command. By this time the

scarcity of forage had reduced the Continental’s horses to below the number

required to drag the artillery, ammunition, provisions and baggage.The

shortage of food and the ongoing command disagreements spelled the end of the

Third Expedition.

On July

11, General Howe called a council of war for his Continental officers and they

resolved to retreat from the St. Marys River, starting July 14. The militia

forces of Houstoun and Williamson had no choice but to follow. Thomas Pickney

stated of the 1778 Florida Expedition, “…before we had taken possession of

Fort Tonyn, which the British abandoned at our approach, more than half of our

troops were in their graves or in the hospitals.”

The

expedition suffered from the same lack of coordination that doomed the

previous two assaults on the southern borderlands. General Howe's Continentals

managed to “capture” Fort Tonyn on the St. Marys River after it was burned and

abandoned by Brown’s Rangers, and Governor Houston’s Georgia Militia were

repulsed by Major Marc Prevost’s Regulars, Florida Rangers and South Carolina

Royal Americans at the Battle of Alligator Creek, which is also the called

Battle of Alligator Creek Bridge. With limited successes and significant

losses due to sickness, the Patriots returned to Savannah.

Alligator Creek

Historical Marker

“SKIRMISH OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION”

June 30, 1778, a force

of 300 American Cavalry commanded by Colonel Elijah Clarke, participating in

General Robert Howe's invasion of Florida, attacked a column of British at

this place (Alligator Creek Bridge), but were unable to penetrate the nearby

entrenchments of 450 British Regulars and South Carolina Royalists under the

command of Major James Marc Prevost. In this skirmish, Colonel Clarke was

wounded and the Americans withdrew. The next day, the British retired in the

direction of the St. Johns River. Casualties: Americans 13 British 9”.

Erected by Jacksonville Chapter, Florida Society Sons of the American

Revolution

Although not specifically located, the site

Battle of Alligator Creek is

believed to have occurred on the

north side of Callahan where U.S. Highway 301 joins with U.S. Highway 1. The

Historical Marker is located on the east side of U.S. Highway 1 in Callahan in

Nassau County, located approximately 20 miles northwest of Jacksonville.

Prepared by Bill Ramsaur, Marshes of Glynn Chapter, Georgia Society Sons of

the American Revolution, Revised 2/15/2014

References:

-

Boatner, Mark M. Landmarks of the American Revolution.

(Harrisburg,

PA: Stackpole Books, 1973)

-

Buker, George E. and Richard A.

Martin. “Governor Tonyn’s Brown-Water Navy: East Florida During The American

Revolution, 1775-1778,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 58,

Issue 1, (July 1979), pp 58-71.

-

Cashin, Edward J (1999). The King's Ranger: Thomas Brown and the American

Revolution on the Southern Frontier (Bronx, New York: Fordham University

Press, 1999)

-

Searcy, Mary. The Georgia–Florida Contest in the American Revolution,

1776–1778 (University, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1985)

-

Smith, Gordon Burns.

Morningstar’s of Liberty: The Revolutionary

War in Georgia 1775-1783, Volume One

(Milledgeville: Boyd Publishing, 2006)

-

Smith, Gordon Burns.

Morningstar’s of Liberty: The Revolutionary

War in Georgia 1775-1783, Volume Two- Georgia Continental Officers During

the Revolutionary War

(Milledgeville:

Boyd Publishing, 2011)

-

Wood, Virginia Steele. “The Georgia Navy’s Dramatic

Victory of April 19, 1778” Georgia Historical Society Quarterly 90,

no 2 (2006) pp 165-195